Coach-built Bristols are a particularly rare breed, with just 38 rolling chassis delivered to various companies for bespoke bodywork; Most notably Touring, Langenthal, Vanden Plas, Beutler, Ghia-Aigle and Pinin Farina. This beautiful 401 is one of a reputed seven such cars bodied by the masters at Farina.

Entering the current ownership in 2022 and sharing a stable with many other early and important Bristols, 401/216 has covered just 2400 miles in his ownership, including trips to various concours events and even a 500-mile trip down to Goodwood and home. The car was previously restored and maintained for its last owner (Andrew Dooley) to an exceptional standard by Spencer Lane-Jones Ltd. In the current ownership, the car has seen further refinements by Creed and Shore Motorworks Ltd.

The Bristol boasts an impressive history file, with unbroken ownership chain, period correspondence and technical literature, receipts and lots of research into this and the sister Farina-bodied cars.

This actual car was the feature of the below six-page article in Classic cars Magazine, penned by Emma Woodcock.

First impressions aren’t everything – just look at this, one of seven Bristol Farinas built. The 401 chassis and running gear are almost entirely factory standard but you wouldn’t know it from the hand-formed bodywork. Styled by Battista ‘Pinin’ Farina, this 1948 machine clothes the Filton mechanicals and chassis in coachbuilt aluminium that encapsulates the best of Italian glamour without losing sight of Bristol Cars’ BMW origins.

HJ ‘Aldy’ Aldington can take credit for the meeting of minds. An enthusiastic racer who’d spent the Thirties selling the best of Bavaria alongside his Frazer Nash sports cars, he introduced Bristol Aeroplane Company directors to BMW and swiftly secured a working relationship, buying blueprints for the 326, 327 and 328 models soon after. Though George White took majority control of the Aldington brothers’ AFN enterprise, HJ remained as managing director and the two firms began work on the Frazer Nash Bristol.

The relationship was fraught. Bristol wanted to refine the pre-existing BMW designs and make steady progress; Aldy thought the post-war age demanded all-new, enveloping styling. The Bristol directors won out and the conventionally Teutonic Bristol 400 entered development, but Aldington wasn’t deterred.

He secured the first two 400 production chassis in late 1946 and drove the unclothed machines over the Alps to the Italian heartland of automotive design. One car went to Touring. the other to Pinin Farina, both were tasked with building something exceptional. Pinin Farina responded by constructing a two-plus-two convertible in stunning contemporary style.

Drawing admiring glances wherever it parks, this dark-blue example shows that the shape still resonates today. There are shades of Lincoln in the gentle swell of the pontoon front wings, intermingled with suggestions of early Ferrari road cars in the way the rear quarters step away, yet Lancia and Alfa Romeo deline the topline and the waterfall bootlid. A reaching pair of chrome ellipses pay homage to the German ancestry but the aluminium panelwork is undeniably Italian. Shared with other Farina designs of the same period, the slim strips mounted to both doors offer a familiar elegance. Pop the inset button and the handle arcs outwards to meet two, maybe three fingers with a delicate hook.

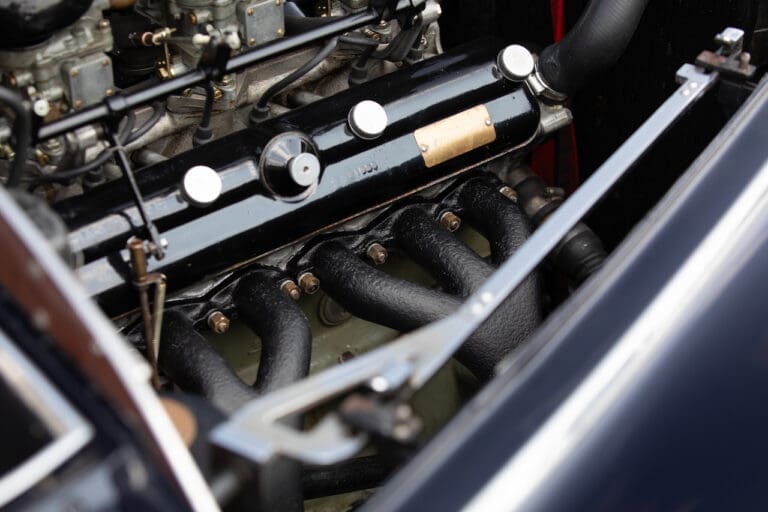

I step up into boundless leather, the fragrance rich and almost sweet, twist the centrally-mounted key and wait for confirmation that this really is a Bristol after all. There’s a short whinny before the 85 series 2.0-litre inline six fires to a wavering idle. The engine snaps to 1500rpm with a barking tenor and I wrap my fingers around the fly-off handbrake and pull, it falls between the flat. Plump seats and the Bristol rolls into the morning rush hour. Even at walking pace, the engine is flexible and obedient with the sharp acoustic edge typical of early Bristols.

A short first gear with freewheel keeps progress smooth but faster, flowing bitumen is a better match for the Bristol, which flies through the intermediate gears before clicking into fourth around 50mph. Ally claimed a top speed of 105mph for the Farina and the most modest 400 could pass go in an age where family cars rarely reached 60mph. Owners could trust a Bristol to maintain speeds too, the firm taking third overall in the 1948 Mille Miglia with a 400 saloon and Aldington driving the first Farina in the 1949 Alpine Rally. Modern traffic is nothing in comparison and the Bristol provides a more relaxed environment than its age might suggest. With the windows raised, the close fitting hood suppresses wind noise and chamfers the exhaust note into a bard-edged murmur, working with an effective heater to keep out the worst of the morning chill. The seating position works well too.

I’m sat low beneath the wheel but high off the road, enjoying good forward visibility while still feeling like I’m inside and not on top of the car. Though the footwell seems narrow, it sits far enough forward for a comfortable driving position and there’s even a cut-out in the clutch pedal that frees up space to rest my left foot.

The dedication to driver comfort matches the radical 1948-forwards 401 saloon from which this Farina takes its chassis, yet the convertible roof transforms the experience. Where the Filton fixed-head feels airy, commodious and curving, the thick sides of the fabric hood shrink the cabin around me and the exposed framework adds to a sense of intimacy. Sunlight sparks off the polished side bars that kink up along the windows, with a subtle arc connecting them just above the bead.

Three clips on the windscreen rail hold the whole assembly in place and the roof folds back below the body line in a simple, three-step movement; the transformation is immediate. Subtract the canvas, lower the side windows and the Farina curves, bucks and seems to drop a couple of inches lower to the road. I can’t take my eyes off the rear haunches and the chrome side strip bisects the body from the sky. Country roads await but for a moment all I can do is take in the shape. Every panel is unique, and many of them vary over the seven-strong production run. The first car wears a more reclined look with a single piece radiator grille surround, while the other six exhibit more pronounced bumpers and front wings that flow further onto the doors. Some boast supplementary driving lights, this example features inset minor griles and at least one has neither. All seven are clothed exclusively in aluminium.

Further differences bide beneath the Pinin Farina body, The Bristol chassis, built to 400 specifcation for the earlier examples and 401 standard for the later cars, was modified to reposition the fuel tank and spare wheel, and the bulkhead is also peculiar to the Farinas. Wider and lower than the standard 400 and 401 items, this spot-welded steel construction was highlighted in period advertising. Steel was used for the substructure, wheelarches and underbody too. The first car was completed in a scant six months yet it emerged to meet a changing Bristol Cars. Disagreements between Aldington and Sir George were reaching their flash point, leading to the dissolution of the Frazer Nash Bristol name and the divestment of AFN. Bristol Cars would focus on its own designs. Ally nevertheless stayed close to Bristol and his family firm became London distributors for the marque. An intricate agreement guaranteed a supply of Bristol engines, allowing Frazer Nash to develop its successful post-war sports cars. Aldington retained his enthusiasm for the Farina project too. The first Farina inspired articles in The Motor and The Autocar, starred in promotional photography and featured in company advertising. “Introduced by Frazer Nash,’ the copy boasts of ‘up-to-the-minute convertible coachwork’ and Pinin Farina’s global reputation. Priced far below the similarly advanced £3400 Lagonda 2.6-litre Drophead Coupé and just above the £2373 Bristol 400 saloon, AFN marketed the Farina at £2500. That could have bought nine Morris Minors. Today the Bristol Farinas are worth far more than any Filton-bodied 400 or 401.

The added value is dear on the road, where roof-down motoring enhances the driving experience. Now the Farina is open to the world, frameless windows leaving no trace once they’ve dropped into the elbow-high door tops. The way the tonneau skims flat with the bodyline increases the sense of space too, setting the car apart from the piled-up constructions favoured by its Alvis TA14, Aston Martin DB 2-litre Sports and Lagonda 2.6-litre competitors.

Pottering past 30mph, the Farina already feels far sportier than its fixed-head sibling. Hot oil and the sticky tang of unburned fuel start to swirl in and, with nothing but sky between me and the single exhaust, the engine takes on a new complexity. The Farina doesn’t seem too certain at first, clunking and whining near idle, but passing 1500rpm releases an industrial growl that smooths into an exhaust-led baritone before reaching 2500rpm.

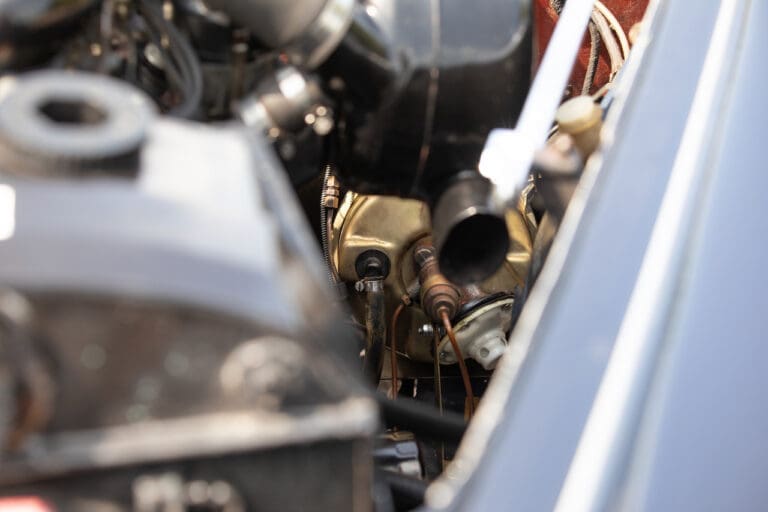

A straight appears, so I push further into the throttle and delve into ever greater aural delights. The Farina shifts tone whenever I add another 500rpm to the dial, its voice so much more multi-dimensional than it seems when the roof is up. The run to 3000rpm brings a simple, rasping precision that smooths soon after into something dual-layered and urgent. Beyond 3500rpm it shifts pitch again, rounding out in an airy battlecry. The soundscape is matched by a responsiveness and surging midrange that reflect Aldy’s original intentions for the Farina drivetrain. All seven cars were equipped with a high-performance 85B variant of the Bristol inline six that used a more aggressive camshaft and raised compression to push power to approximately gsbhp. a meaningful gain on the 95bhp 400 saloon. This car lost its 85B engine in period but its uprated 85C channels the same spirit with Cosworth oversize pistons, a BMW 328 sports camshaft and a 9.51 compression ratio. Freer-revving than the V6 in a Lancia Aurelia and smoother than the Lagonda inline six fitted to Feltham era Aston Martins, it’s a pleasure to use.

As sole agents for London, the wider United Kingdom and all export markets, the Aldington brothers continued to shape the Bristol story. Recent research by Andrew Blow and the Bristol Owners Heritage Trust suggests that AFN dispatched approximately 26 chassis to Europe via Swiss-German intermediary CA Drenowatz, and most received coachbuilt bodywork. Beutler and Langenthal both provided their own interpretations, Touring constructed several cars to its initial 400 design, and Aldington sent a further six Bristols to Pinin Farina between December 1947 and summer 1948.

The history of Chassis 401/716

This car – was one of the last, leaving for Italy on 9 August 1948. Records held by the Bristol Owners’ Club show that the finished car returned in January 1950 and AFN promptly prepared it for sale, fitting 22mm torsion bars, replacing all four wheels and swapping the original 85B/1345 engine for the current BSC/1572 unit. By February of that year the Farina had found an English owner; she fitted a Bristol badge to bootlid and covered more than 10,000 miles in her first year behind the wheel. An extensive overhaul and the fitment of an anti-roll bar followed in 1955 but the service history record then goes dark.

More than three decades later, a Swiss collector contacted the Bristol Owners’ Club. He was selling 401/216. Late club secretary Brian Cuddigan bought it, embarking on a restoration and repaint in signal red. With a sand beige roof and the wood-rimmed steering wheel from a Jaguar E-type, the finished Farina made a head-turning sight at British events until the early 2000s. Chassis 401/216 established itself in print too, appearing in a Nineties classic car encyclopaedia, Charles Oxley’s Bristol: An Illustrated History and one of the marque tomes by LJK Setright.

Later the car departed for sunnier climes, after Andrew Blow brokered its sale to a Portuguese collector. Over the course of his ownership, he drove the Farina throughout Europe, had it repainted dark blue and fitted a matching convertible roof. By 2011 it was once again on for sale. The current keeper – a two-time Bristol owner with a particular interest in post-war Italian coachbuilding – flew out as soon as he saw the advert. Cruising roof down at 2700rpm, car and driver bonded on the journey home from Lisbon to England. It would be the first of many European adventures. Following the installation of front seatbelts and a Spencer Lane-Jones engine rebuild, 401,216 has whisked its occupants to the South of France and over the Picos de Europa mountains. Thanks to a chance encounter with a one-time Bristol employee, the owner has even charted and followed the trans-Alpine route of Aldy’s bare chassis odyssey to Pinin Farina.

Bounding through Wiltshire countryside, the Farina makes for a sophisticated companion. The rack-and-pinion steering acts quickly and consistenty after a minimal deadzone, inspiring more confidence than the less-direct systems fitted to many peers. The wheel barely moves between my fingers, the column dampening vibration at the expense of feel, which works with the soft, slightly underdamped ride to encourage a relaxed driving style.

Raising the pace too far exposes the limitations of the convertible design. Lateral imperfections send the rear axle chattering and pock-marked roads pulse scuttle shake through the steering column. The Lockheed drums aren’t the last word in stopping power, though they’re easy to modulate and bite in just the right place for clean heel-and-toe downshifts. The gearbox is a pleasure too. Its kinked lever reaches close to my left hand and telegraphs clean, precise feedback that rewards snappy shifts.

Ficking back into fourth, I point down off the plains and take a final moment to enjoy the sights and sounds that set the coachbuilt Bristol apart. Stylish hide laps from all around and the Smiths gauges with their jet age font dance in the Farina-specific dashboard, as I peer out along the high-swept, gently curving wings. I click down a gear just to hear the engine sing and I can’t help but smile… Aldington was onto something. The Farina is the best of Bristol with a boutique finish!

PLEASE NOTE – The BRDC Members Badge is to be retained by the seller.

| Chassis Number 410/216 | Engine Number 400/85c/1345 |

| August 1948 | Chassis shipped from AFM to Farina in Milan |

| January 1950 | Returned to AFN engine changed to 400/85c/1571 |

| February 1950 | Mrs K H Maurice Castle Combe Gloucester |

| 1956 | FD Murray Baxter Comely Bank Edinburgh |

| 1970’s – Dec 1987 | F Bloete Caterham Surrey

Red |

| 1990’s | Ex El Hoss Switzerland

Red |

| March 1990 –

Oct 2006 |

Brian Cuddigan Blackheath London

Red |

| July 2004 | June 2007 Andrew Pucher, Queens Gate, London

Red |

| November 2012 | Carlos Cruz Lisbon Portugal

Dark blue |

| September 2011 | Andrew Blow

Dark blue |

| October 2012 | Andrew Dooley Cranbrook Surrey

Dark blue |

| April 2022 – | Our Vendor

Dark blue |